Philip Morris

Contents

- 1 Background

- 2 Employees or Board Members: Past and Present

- 3 Affiliations

- 4 Controversial Marketing Strategies

- 5 Complicity in Tobacco Smuggling

- 6 Tactics to Subvert Tobacco Control Campaigns and Policies

- 7 Next Generation Products

- 8 TobaccoTactics Resources

- 9 Relevant Links

- 10 TCRG Research

- 11 Notes

Background

Philip Morris International (PMI) is the largest tobacco company in the world (excluding the Chinese National Tobacco Corporation).[1] The company is headquartered in New York in the United States (US), but based operationally in Lausanne, Switzerland.[2] PMI was a subsidiary of the Altria Group Inc until 28 March 2008.[2] According to the Associated Press, Altria decided to separate Philip Morris USA and its international operation in order to "clear the international tobacco business from the legal and regulatory constraints facing its domestic counterpart, Philip Morris USA".[3]

In 2015, PMI and its subsidiaries sold its products in over 180 markets, selling cigarettes, other tobacco products and non-combustible nicotine based products.[2] Its global cigarette brands are Marlboro (the world’s bestselling international brand), Merit, Parliament, Virginian S, L&M, Philip Morris, Bond Street, Chesterfield, Lark, Muratti, Next and Red & White.

The company reported owning a market share of at least 15% or over in 103 countries in 2015, although in the UK PMI held only fourth position for cigarette market share behind, Japan Tobacco International (JTI), Imperial Tobacco, and British American Tobacco (BAT).[1]

Employees or Board Members: Past and Present

André Calantzopoulos was appointed as the Chief Executive Officer of PMI in May 2013.[4]

A full list of the company’s leadership team can be accessed at PMI’s website.

Other persons that currently work for, or have previously been employed with, the company:

Chris Argent | Drago Azinovic | Martin J. Barrington | David Bernick | Bertrand Bonvin | Harold Brown | Patrick Brunel | Mathis Cabiallavetta | Louis C. Camilleri | Andrew Cave | Herman Cheung | Kevin Click | Marc S. Firestone | John Dudley Fishburn | Jon Huenemann | Even Hurwitz | Martin King | Jennifer Li | Graham Mackay | Sergio Marchionne | Kate Marley | Kalpana Morparia | Jim Mortensen | Lucio A. Noto | Jacek Olczak | Matteo Pellegrini | Robert B. Polet | Ashok Rammohan | Carlos Slim Helú | Julie Soderlund | Hermann Waldemer | Jerry Whitson | Frederic de Wilde | Stephen M. Wolf | Miroslaw Zielinski

Affiliations

Memberships

In 2016, PMI was a member of the following organisations:[5]

The American Chamber of Commerce to the European Union | American European Community Association (AECA) | International Trademark Association (INTA) | The Trans-Atlantic Business Council (TABC) | European Policy Centre (EPC) | Kangaroo Group | European Risk Forum | BusinessEurope | European Smokeless Tobacco Council (ESTOC) | British Chamber of Commerce | VBO-FBE | Public Affairs Council | APRAM | LES France | European Communities Trademark Association (ECTA) | MARQUES | AmCham Germany | Bund fur Lebensmittelrecht & Lebensmittelkunde | Europaischer Wirtschaftssenat (EWS) | Wirtschaftsbeirat der Union e.V. | American Chamber of Commerce of Estonia | American Lithuanian Business Council | Lithuanian Confederation of Industrialists | Investors’ Forum | AmCham Spain | CEOE | Spanish Tobacco Roundtable | Ass. Industrial Portuguesa (AIP) | Centromarca | Unindustria (Confindustria) | Economiesuisse | Consumer Packaging Alliance | British Brands Group | Foodstuff Chamber | Czech Association of Branded Goods

The company was also a member of the Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing Foundation (ECLT).[6] The ECLT has a partnership with the International Labour Organization (ILO), a United Nations (UN) agency, focussed on issues related to labour such as international labour standards, social protection and unemployment.[7]

PMI was a member of the Confederation of European Community Cigarette Manufacturers (CECCM), but left in 2006 following a dispute with other members.[8]

Consultancies

PMI has worked with numerous Public Relations (PR) and law consultancies, including:

- In 2016, Philip Morris UK was a client of London-based PR and communications company Instinctif Partners.

- That same year, media also linked Brussels-based PR company Pantarhei Advisors to Philip Morris.

- IN 2014, UK-based Media Intelligence Partners were PMI's media contact during Sir Cyril Chantler's plain packaging review.

- In 2014, German PR company Communications & Network Consulting AG (CNC) listed Philip Morris as a client on the EU Transparency Register.

- In that same year, Luxembourg-based Felula SA, a one-person consultancy run by Serge Estgen, listed PMI as its client on the EU Transparency Register.

- In 2013, Edinburgh-based Halogen Communications supported PMI's opposition to Scotland's plans to introduce Plain Packaging.

- In 2012 and 2013, PMI worked with London-based PR and media company Pepper Public Affairs on PMI's Anti-Plain Packaging Campaign.

- In 2012, the UK branch of Crosby Textor Group, helped PMI oppose Plain packaging in the UK.

- Law firm Clifford Chance has a history of lobbying for PMI in the UK and European Union (EU). In 2009, the firm submitted anonymous Freedom of Information requests to a UK university on behalf of the tobacco company, and in 2011 and 2012 Clifford Chance's Michel Petite lobbied on the EU Tobacco Products Directive.

- From 2009 to 2011 PR company Gardant Communications worked for Philip Morris UK. In 2009, the PR company supported Philip Morris' PR Campaign Against the Display Ban and was involved in Philip Morris' Regulatory Litigation Action Plan Against the Display Ban.

- APCO Associates' collaboration with PMI goes back to the 1990s when it helped the company set up the European Science and Environment Forum. More recently, it was involved in Philip Morris' PR Campaign Against the Display Ban.

- London-based PR company INHouse Communications also played a part in Philip Morris' PR Campaign Against the Display Ban.

- Ogilvy Group's collaboration with Philip Morris goes back to the 1950s when it ran one of its advertising campaigns.

Controversial Marketing Strategies

Targeting Youth

PMI says that they are “committed to doing our part to help prevent children from smoking or using nicotine products”. [9]

They further state that their “marketing complies with all applicable laws and regulations, and we have robust internal policies and procedures in place so that all our marketing and advertising activities are directed only toward adult smokers”.[9]

Despite these assurances, PMI has been accused of, and fined for, running marketing campaigns that target young people.

In 2014, PMI was fined more than US$ 480,000 in Brazil over its Be Marlboro campaign, which has been strongly criticised for deliberately targeting youth.[10][11] The campaign was first launched in 2011 in Germany to promote PMI’s revamped Marlboro brand, and was rolled out in more than 50 countries. Germany banned the campaign in 2013, reportedly ruling that “[the ads] were designed to encourage children as young as 14 to smoke”.[12]

Images 1 to 5 show examples of the Be Marlboro campaign. All images were taken from a 2012 presentation by the tobacco company’s Senior Vice President of Marketing and Sales, Frederic de Wilde.[13]

More details and images of the campaign can be found on our Be Marlboro: Targeting the World's Biggest Brand at Youth page.

PMI's controversial practices do not only apply to the marketing of the company's combustible products.Concerns were raised about a proposed marketing strategy that PMI planned to use to launch Parliament snus in Russia in 2012.[14] The proposed advertising materials, made public by advertising firm Proximity Russia, included materials that were clearly titled “advanced youth engagement materials”.[14]

For more information on this campaign, and images of the marketing materials, visit our page on Snus: Marketing to Youth.

Complicity in Tobacco Smuggling

PMI portrays itself publicly as a victim of illicit tobacco trade, with the company reporting that tobacco smuggling results in “loss in sales”, and “damages our brand”.[15]

To help tackle illicit trade, PMI launched a funding initiative called PMI IMPACT, worth US$100m and aimed at bringing together “organisations that fight illegal trade and related crimes, enabling them to implement solutions”.[16] In its first call for proposals in 2016, PMI asked for “projects that have an impact on illegal trade and related crimes in the European Union…”[17]

In contrast to the company’s public persona of being part of the smuggling solution, evidence shows that the company was, in fact, part of the problem. In 2000, the European Commission (backed by a majority of EU member states) started court proceedings in the US Courts against PMI and other tobacco companies for its complicity in tobacco smuggling.The Commission claimed that the tobacco companies “boosted their profits in the past by deliberately oversupplying some countries so that their product could be smuggled into the EU”, costing the EU millions of euros in lost tax and customs revenue.[18][19]

PMI and the Commission settled their dispute in 2004, when the company agreed to pay the Commission £675m to fund anti-smuggling activities.[20] The two Parties signed an Anti-Counterfeit and Anti-Contraband Cooperation Agreement,[21] referred to by the company as Project Star. As part of this agreement, PMI commissioned KPMG to measure annually the size of the legal, contraband and counterfeit markets for tobacco products in each EU Member States.

Project Star’s methodology and data have been strongly criticised for lack of transparency, overestimating illicit cigarette levels in some European countries, and serving PMI's interests over those of the EU and its member states.[22]

Tactics to Subvert Tobacco Control Campaigns and Policies

PMI has strongly opposed tobacco control legislation and regulations across the world, including plain packaging in Australia and the UK, the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), and tobacco control decrees in Uruguay. The company has used a variety of strategies and tactics to influence tobacco control policies, and subvert existing regulations.

Funding Pro-Tobacco Research and Discrediting Independent Evidence

In response to plain packaging proposals in the UK, PMI funded research, expert opinion and public relations activities which supported its position. One of the people that PMI funded for this purpose was Will O’Reilly, a former Detective Chief Inspector with the London Metropolitan Police.

O’Reilly was appointed as a PMI consultant in 2011,[23] conducting undercover test purchases of illicit tobacco and publicising his findings in UK regional press. One of PMI's arguments to oppose plain packaging, was that the public health measure would lead to an increase in illicit tobacco, including counterfeited plain packs. For background on, and a critique of, this argument, go to Countering Industry Arguments Against Plain Packaging: It will Lead to Increased Smuggling. O’Reilly’s test purchases appear to have enabled PMI to secure significant press coverage of its data on illicit tobacco.[24]

Other organisations and individuals that have received funding from PMI to produce research or expert opinions or critiques of independent evidence, in order to oppose tobacco control legislation are:

Deloitte | KPMG | Transcrime | Roy Morgan Research | Ashok Kaul | Michael Wolf | Populus | Centre for Economics and Business Research[25][26] | Compass Lexecon[27] | Rupert Darwall[28] | James Heckman [29] | Lord Hoffman[30] | Alfred Kuss[31] | Lalive [32] | LECG[33][34][35] | London Economics | Povaddo[36] | SKIM Consumer Research[37]

- For more information on the tobacco industry’s use of research to undermine legitimate independent evidence see: Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Funded Research, Expert Opinion and Public Relations.

Using Freedom of Information Requests to Acquire Public Health Research Data

Freedom of Information (FOI) requests are one strategy that the tobacco industry use to undermine tobacco control legislation, often covertly using third parties.[38]

In 2009, and again in 2011, PMI sent Freedom of Information requests to Stirling University (UK) requesting access to a wide range of data from its research on teenage smoking. PMI alleged that it wanted “to understand more about the research project conducted by the University of Stirling on plain packaging for cigarettes”.[39] The FOI requests were eventually dropped.

For more information on these FOI requests, and an explanation on how these requests impacted the University of Stirling, go to our page FOI: Stirling University.

Fabricating Support through Front Groups

PMI has used front groups to oppose tobacco control measures. Front Groups are organisations that purport to serve a public interest, while actually serving the interests of another party (in this case the tobacco industry), and often obscuring the connection between them.

In Australia, leaked private documents revealed that the supposed anti-plain packaging retailer grass roots movement, the Alliance of Australian Retailers was set up by tobacco companies and that the Director of Corporate Affairs Philip Morris Australia, Chris Argent, played a critical role in its day-to-day operations.[40][41][42]

- For more information on this front group, and Philip Morris Australia’s involvement, visit the Alliance of Australian Retailers page.

Lobbying of Decision Makers

EU

PMI reported that it spent between €1,250,000 and €1,499,999 in 2015 lobbying EU institutions, employing only 1.5 fulltime equivalent staff in its Brussels office.[43] If this data is correct, it suggests that PMI relied heavily on external lobbying firms.

A 2013 leaked internal PMI document revealed that the company had 161 lobbyists working to undermine the revision of the EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD).[44] The objective of PMI’s campaign was to either ‘push’ (i.e. amend) or ‘delay’ the TPD proposal, and ‘block’ any so-called ‘extreme policy options’ like the proposed point of sales display ban and plain packaging.[45]

- For more information on PMI’s campaign to undermine the TPD, go to EU Tobacco Products Directive Revision and PMI Mobilised Support from Retailers.

UK

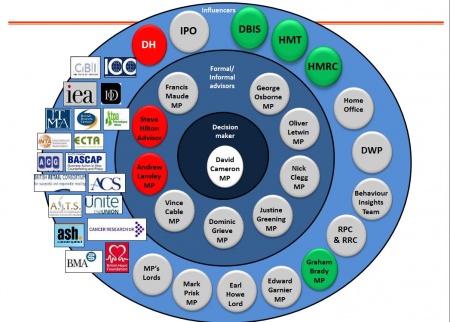

The leaked internal PMI documents also revealed the extent of a multi-faceted campaign against Plain Packaging in the UK, including a detailed media campaign using dozens of third parties (both individuals and organisations) to promote its arguments against the policy. The documents also included a detailed political analysis of potential routes of influence for the tobacco company(Image 6).[23]

One third party appointed in November 2011 to help PMI oppose the plain packaging proposal was the Crosby Textor Group. This appointment led to a conflict of interest scandal given that Lynton Crosby co-Director of the Crosby Textor Group, was also the political election strategist for the UK’s Conservative Party when they were the political party in power in the UK. David Cameron, then head of the Conservative Party and UK Prime Minister, insisted that Crosby never lobbied him about plain packaging. [46][47] Despite a lack of evidence that Crosby lobbied the Prime Minister and Health Minister on plain packaging, documents released under FOI legislation, obtained by the University of Bath Tobacco Control Research Group, show that Crosby lobbied the UK Government on plain packaging via Lord Marland, the then Parliamentary Under Secretary of State for Intellectual Property, to oppose plain packaging. For more information on this lobbying scandal, go to Lynton Crosby’s page.

- For more detail on PMI's attempts to undermine plain packaging proposals in the UK, visit

- PMI Mobilised Support from Retailers | PMI's Anti-Plain Packaging Lobbying Campaign | PMI’s Anti-PP Media Campaign | PMI’s “Illicit Trade” Anti-Plain Packaging Campaign

- For information on the tobacco industry's tactics to undermine this tobacco control measures, visit our pages on:

- Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Company Opposition | Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Funded Research, Expert Opinion and Public Relations | Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Built Alliances | :Plain Packaging in the UK: Tobacco Industry Funded Third Party Campaigns

- PMI also opposed the tobacco product display ban gradually introduced in the UK from 2012. More information on PMI’s tactics to stop this measure, see:

- Philip Morris' Regulatory Litigation Action Plan Against the Display Ban | Philip Morris' PR Campaign Against the Display Ban

Intimidating Governments with Litigation or Threat of Litigation

PMI has legally challenged tobacco control regulations in the UK, EU, Uruguay and Australia, including:

- Ordinance 514, dated 18 August 2008, and Decree 287/009 dated 15 June 2009 (Uruguay). PMI unsuccessfully challenged the Uruguayan Tobacco Control Act which included a mandate for 80% health warnings on tobacco packets.[48] PMI brought its claim under the Switzerland-Uruguay Bilateral Investment Treaty at the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes. The tribunal ruled in favour of Uruguay in July 2016.[49]

- The Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (Australia). PMI fiercely opposed this piece of legislation, fearing that it may set a global precedence. The company fought this legislation unsuccessfully on three fronts:

- World Trade Organization (WTO) challenge: In 2014, PMI supported a request by the Dominican Republic government before the WTO Dispute Settlement Body, alleging that Australia’s plain packaging laws breach the WTO’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) and agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS).[50] Similar requests were submitted by Ukraine, Cuba, Indonesia and Honduras, and furthermore, a record number of more than 40 WTO members joined the dispute as third parties.[51]

- Constitutional challenge: In March 2012, PMI supported a claim made by British American Tobacco (BAT) in Deceber 2011 before the Australian High Court that plain packaging was in breach of the Australian constitution.[52] On 15 August 2012, the Hight Court ruled that plain packaging was not in breach with the Australian constitution as there had been no acquisition of property as alleged by the tobacco companies.[51]

- Bilateral Investment challenge: In 2011, PMI started legal proceedings against the Australian government for allegedly violating the terms of The Australia – Hong Kong Bilateral Investment Treaty.[53] In December 2015, The Permanent Court of Arbitration issued a unanimous decision that it had no jurisdiction to hear the claim.

- For more information, on both claims go to Australia: Challenging Legislation.

- The Standardised Packaging of Tobacco Products Regulations 2015 (UK). Following the passage of the legislation in March 2015, PMI and others launched a legal action, which it lost in May 2016 (the day before the legislation was due to come into force).[54][55]

- The 2014 EU Tobacco Products Directive (TPD). PMI and BAT attempted to invalidate the TPD as a whole, or various provisions within it, but this legal challenge was dismissed in the European Court of Justice in May 2016.[56] More details can be found on the page TPD: Legal Challenges.

Next Generation Products

To improve the tobacco industry’s sustainability, tobacco companies are investing in tobacco and nicotine products that, unlike cigarettes, could have growth potential in developed markets. These products are often referred to as Next Generation Products (NGPs), and are often linked to tobacco companies’ harm reduction strategies. In January 2017, PMI issued a press release which stated that the company intended to move its business away from combustible tobacco products entirely.(Image 7)[57] In April 2019 a life insurance company Reviti was launched. It is a wholly-owned subsidiary of PMI. The London-based company specialises in offering policies to smokers, with discounts for those who reduce or switch to PMI’s Next Generation Products. For more information on these products go to E-Cigarettes: Philip Morris International and Heated Tobacco Products.

In September 2017, the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World was formally launched at the Global Tobacco and Nicotine Forum 2017, a tobacco-industry funded event.[58][59] The Foundation for a Smoke-Free World describes itself as “an independent, private foundation formed and operated free from the control or influence of any third party”, which “makes grants and supports medical, agricultural, and scientific research to end smoking and its health effects and to address the impact of reduced worldwide demand for tobacco”.[60][61] The Foundation is entirely funded by PMI to the tune of US$1 billion.[60] Derek Yach leads the Foundation and is the former Head of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Tobacco Free Initiative. He was also Senior Vice President of Global Health and Agriculture Policy at the global sugary drinks giant PepsiCo.[62]

Futuro sin Humo campaign in Mexico

Futuro sin Humo (Smoke-free Future in English) is a Philip Morris International initiative[63] from its Mexico office to promote their line of Next Generation Products. The initiative was launched in 2018, along with the hashtag #futurosinhumo, which translates into "smoke-free future". Its website describes it as a

“movement is to inform and give voice to smokers and their over-18 years old relatives who are interested in the non-combustion alternatives that are now available in many other countries. We are sure that smokeless products are a better choice for smokers and their introduction in Mexico must be preceded by a debate that includes all stakeholders and is based on scientific evidence.”[64]

For more information about the campaign and its use of celebrities, social media marketing and sports events see Futuro sin Humo.

TobaccoTactics Resources

- PMI Mobilised Support from Retailers

- PMI's Anti-Plain Packaging Lobbying Campaign

- PMI’s Anti-PP Media Campaign

- PMI’s “Illicit Trade” Anti-Plain Packaging Campaign

- Philip Morris vs the Government of Uruguay

- Philip Morris' PR Campaign Against the Display Ban

- Philip Morris' Regulatory Litigation Action Plan Against the Display Ban

- Philip Morris' Marlboro Brand Architecture

- Codentify

- Digital Coding & Tracking Association (DCTA)

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World

- Foundation for a Smoke-Free World: How it Frames Itself for a detailed analysis of the ways in which the Foundation portrays itself and those who oppose the Foundation, plus the counter evidence to these portrayals.

Relevant Links

- Philip Morris International company website

- Cancer Council Australia's Critiques of KPMG Australia illicit tobacco trade reports

TCRG Research

- Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: a review of the PMI funded ‘Project Star’ report, A. Gilmore, A. Rowell, S. Gallus, A. Lugo, L. Joossens, M. Sims, 2013, Tobacco Control, doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051240

- Transnational tobacco company interests in smokeless tobacco in Europe: Analysis of internal industry documents and contemporary industry materials, S. Peeters, A. Gilmore, PLoS Medicine, 2013,10(9):1001506

- Illicit trade, tobacco industry-funded studies and policy influence in the EU and UK, G, Fooks, S. Peeters, K. Evans-Reeves, Tobacco Control, 2014,23(1):81-83

- ‘It will harm business and increase illicit trade’: an evaluation of the relevance, quality and transparency of evidence submitted by transnational tobacco companies to the UK consultation on standardised packaging 2012, K. Evans-Reeves, J. Hatchard, A. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2015,24(e2):e168-e177

- The revision of the 2014 European tobacco products directive: an analysis of the tobacco industry's attempts to ‘break the health silo’, S. Peeters, H. Costa, D Stuckler, M. McKee, A. Gilmore, Tobacco Control, 2016,25(1):108-117

Notes

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Philip Morris International. 2015 Annual Report. 2016, PMI:New York

- ↑ Associated Press, 'Altria to spin off Philip Morris International', MSNBC website, 29 August 2007, accessed 19 February 2012

- ↑ PMI, Who we are: Our leadership Team, Philip Morris International website, accessed February 2017

- ↑ European Commission Transparency Register Philip Morris International Inc, Transparency Register, last updated 25 April 2016, accessed March 2017

- ↑ The Eliminating Child Labour in Tobacco Growing Foundation, ECLT Foundation Governance, 2017, accessed November 2017

- ↑ International Labour Organization, Mission and impact of the ILO, 2017, accessed November 2017

- ↑ L. Polomé, Email to Anna Gilmore from CECCM Office Assistant, 23 June 2009

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Philip Morris International,Underage Tobacco and Nicotine Use, PMI website, undated, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Editor, Philip Morris International Fined in Brazil for Targeting Youth with its “Be Marlboro” Ads, 28 August 2014, Campaign for Tobacco-Free Kids website, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids, Maybe you’re the target: New global Marlboro campaign found to target teens, March 2014, accessed March 2017

- ↑ S. Bosely, Marlboro marketing campaign aimed at young people, anti-tobacco report says, The Guardian, 12 March 2014, accessed March 2017

- ↑ F. de Wilde, Philip Morris International Investor Day – Brand Portfolio and Commercial Approach, 21 June 2012

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 S. Peeters, K.Evans, Russia: snus targeted at young & wealthy, Tobacco Control , 2012; 21:456-459, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Philip Morris International, Illicit Trade – Impact on Or Business, undated, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Philip Morris International, PMI Impact, undated, accessed March 2017

- ↑ PMI, Explore: Theme for first funding round, PMI IMPACT, accessed June 2016

- ↑ A. Osborn, European court rules against tobacco manufacturers, The Guardian, 16 January 20103, accessed March 2017

- ↑ D. Lumsden, PMI Pays £675m to combat smugglers, The Telegraph, 10 July 2004, accessed March 2017

- ↑ D. Lumsden, PMI Pays £675m to combat smugglers, The Telegraph, 10 July 2004, accessed March 2017

- ↑ European Commission, Anti-contraband and anti-counterfeit agreement and general release between Philip Morris International, Philip Morris Products, Philip Morris Duty Free, and Philip Morris Trade Sarl, the European Community represented by the European Commission and each Member State listed on the signature pages hereto, 9 July 2004

- ↑ A. Gilmore, A. Rowell, S. Gallus et al.Towards a greater understanding of the illicit tobacco trade in Europe: A review of the PMI funded Project Star report, Tobacco Control 2014;23:e51-e61

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Philip Morris International, Corporate Affairs Update, March 2012, Leaked document

- ↑ K. A. Evans-Reeves, J. L. Hatchard, A. Rowell et al. Content analysis of tobacco industry data on the illicit tobacco trade in UK newspapers during the standardised packaging debate. Public Health Science Conference Abstract 25 November 2016, The Lancet, Volume 388, Supplement 2

- ↑ Centre for Economics and Business Research, Quantification of the economic impact of plain packaging for tobacco products in the UK, March 2013, accessed June 2016

- ↑ Centre for Economics and Business Research, Quantification of the economic impact of plain packaging for tobacco products in the UK – Addendum to the report for Philip Morris Ltd, August 2013, accessed June 2016

- ↑ Compass Lexecon, Summary assessment of Plain Tobacco Packaging: a systematic review Annex 2, May 2012, accessed June 2016

- ↑ R. Darwall, Selecting the evidence to fit the policy: An evaluation of the Department of Health’s consultation on standardised tobacco packaging, January 2013, unavailable online

- ↑ J Heckman, Report of James J Heckman UK Plain Packaging Consultation Annex 4, August 2012, accessed June 2016

- ↑ Lord Hoffman, Lord Hoffman Opinion, May 2012, accessed June 2016

- ↑ A. Kuss, Comments concerning Annex 2 “Elicitation of subjective judgements of the impact of smoking of plain packaging policies for tobacco products” of the IA No. 3080 “Standardised packaging for tobacco products”, August 2012, accessed June 2016

- ↑ Lalive, Why Plain Packaging is in Violation of WTO Members’ International Obligations under TRIPS and the Paris Convention, July 2009, accessed June 2016

- ↑ LECG, A critical review of the literature on generic packaging for cigarettes, November 2008, accessed June 2016

- ↑ LECG, The impact of plain packaging of cigarettes in Australia: A simulation exercise, February 2010, accessed June 2016

- ↑ LECG, The impact of plain packaging of cigarettes in UK: a simulation exercise, Annex 2, Philip Morris International’s input to the public consultation on the possible revision of the Tobacco Products Directive 2001/37/EC, November 2010, accessed June 2014

- ↑ Povaddo, National Association of Retired Police Officers (NARPO) Survey, November 2012, accessed June 2016

- ↑ SKIM Consumer Research, The impact of standardised packaging on the illicit trade in the UK summarised in SKIM conducted UK study about tobacco buying behavior for Philip Morris International, no date

- ↑ G. Dimopoulos, A. Mitchell, T. Voon. [https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2725638 The Tobacco Industry’s Strategic Use of Freedom of Information Laws: A Comparative Analysis (30 September 2015). Oxford University Comparative Law Forum (2016), Forthcoming

- ↑ S. Connor, "Exclusive: Smoked out: tobacco giant's war on science - Philip Morris seeks to force university to hand over confidential health research into teenage smokers," The Independent, 1 September 2011, accessed March 2017

- ↑ C. Argent, Email from Chris Argent to Jason Aldworth regarding submission of a proposal, 27 May 2010 19:04:15, Truth Tobacco Industry Documents, Bates no: plain0001-plain00002, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Anne Davies, 'Big Tobacco hired public relations firm to lobby government', Sydney Morning Herald, 11 September 2010, accessed March 2017

- ↑ The Tobacco Files -A definitive conclusion to the debate over plain-packaging, no date

- ↑ European Commission Transparency Register, Philip Morris International Inc., last modified on 25 April 2016, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Philip Morris International, Copy of new Transparency Register – List of consultants and their expenses. Undated. Leaked document

- ↑ Philip Morris International. EU Tobacco Products Directive Review, 17 August 2012. Leaked document

- ↑ A. Grice, Smoking gun? David Cameron dodges Lynton Crosby cigarette packaging controversy question, The Independent, 17 July 2013, accessed March 2017

- ↑ BBC News, Ed Miliband demands Lynton Crosby ‘conflict of interest’, 17 July 2013, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Request for arbitration 19 February 2010, italaw, accessed March 2017

- ↑ M. Castaldi, A. Esposito, Philip Morris loses tough-on-tobacco lawsuit in Uruguay, Reuters, 8 July 2016, accessed March 2017

- ↑ A. Martin, Philip Morris leads plain packs battle in global trade arena, 22 August 2013, Bloomberg news, accessed March 2017

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Attorney-General's Department, Tobacco plain packaging- investor-state arbitration, Australian Government website, undated, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Philip Morris Ltd's Submissions (Intervening), 26 March 2012, High Court of Australia website, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Allens Arthur Robinson, Written Notification of Claim Austrralia/ Hong Kong Agreement for the Promotion and Protection of Investments, 27 June 2011, accessed March 2017

- ↑ A. Ram, Tobacco giants launch UK packaging challenge, 8 December 2015, The Financial Times (by subscription), accessed April 2016

- ↑ PMI v Secretary State for Health Judgement, Royal Courts of Justice, Mr Justice Green, 19 May 2016, accessed March 2017

- ↑ A. Glahn, ENSP welcomes the European Court of Justice’s decision to reject challenges against the Tobacco Products Directive, 2 December 2016, European Network for Smoking and Tobacco Prevention website, accessed March 2017

- ↑ PMI, Philip Morris International looks toward a smoke-free future, PMI Press Release, 17 January 2017, accessed March 2017

- ↑ Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Media Advisory: Foundation Forming to Eliminate Smoking Worldwide, 12 September 2017, accessed September 2017

- ↑ Global Tobacco & Nicotine Forum 2017 New York City, USA, September 12-14, 2017, accessed September 2017

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, About Us, accessed May 2018

- ↑ D. Yach, The State of Smoking 2018 Global survey findings and insights, Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Press Conference Presentation, 19 March 2018, accessed May 2018

- ↑ Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Foundation leadership, 2018, accessed May 2018

- ↑ Phillip Morris Mexico,Preguntas Frecuentes, 2018, accessed April 2019

- ↑ Futuro Sin Humo website,Futuro Sin Humo, 2018, accessed April 2019

- Tobacco Companies

- Philip Morris International

- Altria

- Legal Strategy

- Challenging Legislation

- Lobbying Decision Makers

- Third Party Techniques

- Countering Critics

- Arguments and Language

- Advertising Strategy

- Hiring Independent Experts

- Influencing Science

- Freedom of Information Requests

- Leaked Tobacco Industry Documents

- Smuggling

- Front Groups

- Plain Packaging

- Harm Reduction

- Tobacco Products Directive

- Next Generation Products

- Snus

- E-Cigarettes

- Heated Tobacco Products

- EU

- UK

- USA

- Brazil

- Germany

- Uruguay

- Mexico